Before Seattle became a city known for tasting menus, coffee culture, and food trends, it learned how to eat at Pike Place Market.

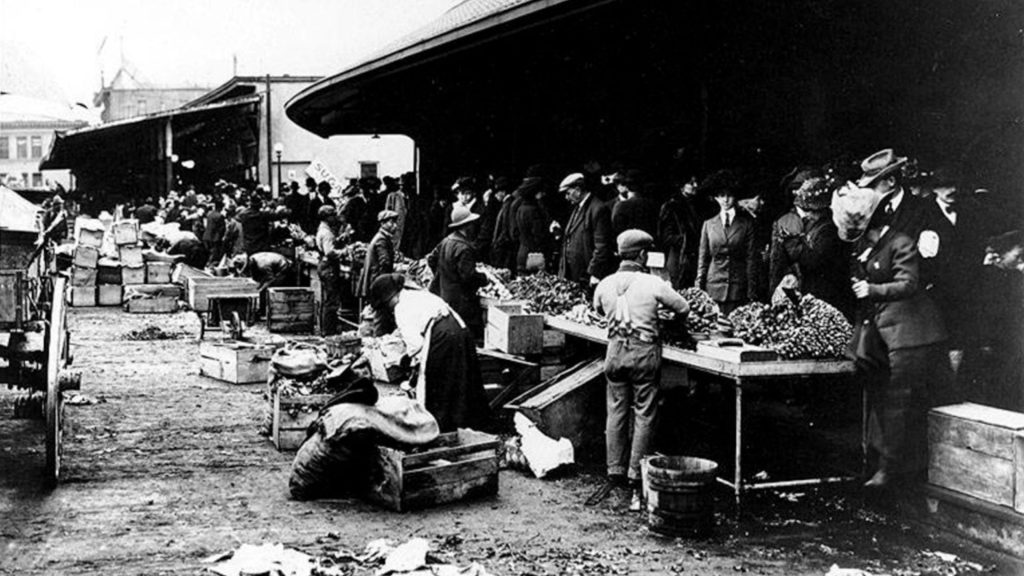

When the market opened in 1907, it was not charming or iconic. It was urgent. Food prices were rising fast, farmers were being squeezed by wholesalers, and everyday Seattleites were paying more for less. Pike Place Market was created as a direct solution. Cut out the middlemen. Put food straight into people’s hands.

On opening day, farmers backed wagons full of apples, berries, potatoes, and onions onto Pike Place. By the end of the morning, nearly everything was gone. The idea worked immediately because the food was fresher, cheaper, and local in a way the city had never experienced.

Seafood quickly became the market’s backbone. Puget Sound salmon, still glistening from the water, was sold whole on beds of ice. Clams and oysters arrived daily from nearby tidelands. Long before sustainability was a buzzword, the market reflected the rhythms of local fishing seasons. What was caught that morning was what you ate that night.

Meat and dairy stalls followed. Whole animals were butchered on site. Eggs arrived unwashed and unrefrigerated. Butter and cheese were sold by weight. This was not curated or polished. It was practical food shopping in a growing working city.

Immigrant vendors changed the market’s flavor forever. Italian grocers introduced olive oil, pasta, and cured meats. Chinese and Japanese vendors sold unfamiliar produce and preserved foods that slowly became part of Seattle kitchens. Spices, dried beans, noodles, and specialty ingredients widened what home cooking looked like in the region.

Bread became another anchor. Small bakeries turned out crusty loaves, sweet pastries, and daily staples that fed dockworkers and families alike. Later, Pike Place Market would become home to the city’s most famous bakery counter, where long lines still form for warm loaves and sticky buns.

The fish throwing that draws crowds today started as efficiency, not performance. Tossing fish across crowded counters saved time and kept orders moving. It was loud, fast, and messy, just like the market itself.

By the mid twentieth century, supermarkets threatened places like Pike Place Market. Convenience nearly replaced connection. When the market faced demolition in the 1960s, it was food that saved it. People did not want to lose access to farmers, fishmongers, and small food businesses that fed the city in a way chains never could.

Today, Pike Place Market still sells what Seattle eats. Seasonal fruit. Fresh seafood. Handmade bread. Foods shaped by immigration, geography, and time. The stalls may be smaller and the crowds larger, but the purpose remains the same.

Pike Place Market did not just feed Seattle. It taught the city what fresh food should feel like.